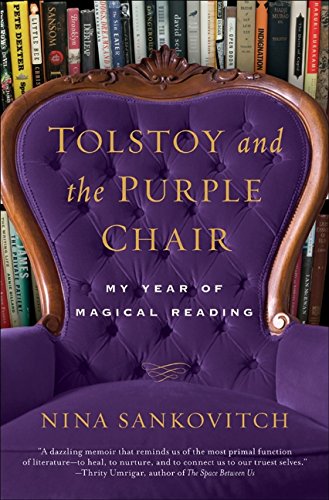

by Nina Sankovitch

The subtitle of Sankovitch’s book is “My Year of Magical Reading,” and it must have been a magical year for her: she read a new book each day and then posted a review of it on her website. Because of my own reading/review project here at Reading Salon, I wish I could have read some of her reviews (how detailed were they? how critical?), but her website—moving on from 2011—is now devoted to marketing more recent books she’s published.

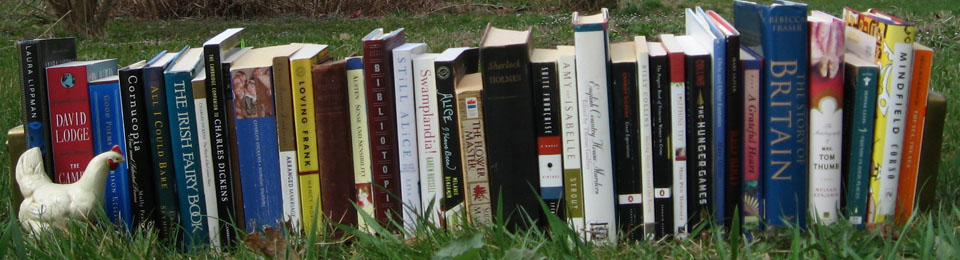

Fair enough; I’ve obviously had this book on my list for some time. In the way of reading serendipity—a magic I can’t help but believe in—“Purple Chair” turned out to be an ideal book to begin my own new year of books, reading, and reviewing. I’m not going to read a book a day, and I certainly don’t want to choose my books based on their page count, as Sankovitch did in order to stick to her goal. I would, however, like to make my reading more organized and meaningful this year: fewer mysteries, more diversity, history, and poetry. (I’m still working through the details.)

Sankovitch used her 365 books project to combat grief after her older sister Anne-Marie had died of cancer three years earlier, at age forty-six. The chair of the title describes her designated reading spot, and Tolstoy was the author whose work, The Forged Coupon, seemed to have the most profound message:

I realized that Tolstoy was laying out an explanation for everything that had happened to me, and setting forth the meaning of my life. The events I had experienced . . . set the contours of my life. But the meaning of my life is ultimately defined by how I respond to the joys and the sorrows, how I forge crossbars of connection and experience, and how I extend help to others as they travel on their own winding road of existence.

Not everyone has the luxury of stepping outside of day-to-day obligations to read and write for a year; Sankovitch has no job to hold down, no apparent worries about money, and even a Brazilian “friend” who comes in to clean every two weeks. Most of us must deal with sorrow in the midst of the messy everything-else, from unsympathetic bosses to unpaid bills. However, no one, whether privileged or impoverished, is immune to sorrow. Sankovitch’s determination to conquer her grief through a marathon-style version of bibliotherapy should strike a chord with anyone who knows that words on a page can indeed serve as guides to one’s life.

The power of inspiration is a beautiful thing, and can indeed be multifaceted. Lovely review.